Leading Astrophysicist/Theologian Addresses University Community

Can Faith and Science be Reconciled?

What happens when some of the best thinking on theology and science coalesce in one person’s exploration of the universe and God’s role in it?

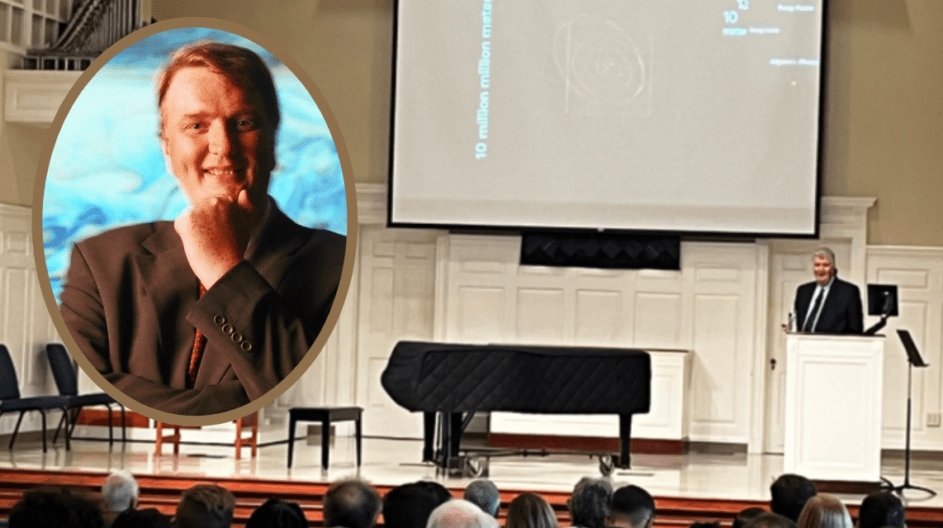

Hundreds of students, faculty and staff found out in November when Dr. David Wilkinson, of the United Kingdom, presented a fascinating multimedia lecture in Henry Pfeiffer Chapel.

The lecture – titled “Hawking, the Big Bang, and the Goldilocks Enigma: The Search for God in Modern Cosmology” – reflected Wilkinson’s highly unusual background. He holds doctorates in systematic theology and in astrophysics. After training for the Methodist ministry at Cambridge University, he pastored a church in Liverpool, England, and he served as the chaplain of Liverpool University. He’s now the Principal of St. John’s College, Durham University, where he’s also a Professor in the Department of Theology and Religion.

Wilkinson’s doctoral research in theology explored Christian eschatology, a part of theology defined as “death, judgment, and the final destiny of the soul and of mankind.” His doctoral research in theoretical astrophysics focused on star formation, the chemical evolution of galaxies, and terrestrial mass extinctions, including the event that wiped out the dinosaurs. He has authored several books on the relationship between science and religion, and he has also written on the relationship of theology to contemporary culture.

After delivering his lecture, Wilkinson conversed with The Falcon Connection on a range of topics, from the role that Methodism plays in his Christian faith to the ways in which he integrates science with theology.

Dr. Wilkinson, thank you for granting us an interview. I understand that you became a Christian when you were 17. Do you imagine that your life as a Christian would have turned out the way it did if you had not been Methodist? Did Methodism fuel your Christianity?

I owe the Methodist tradition a great deal in terms of my development as a Christian. I worship every week at a Methodist church. And that’s where a great deal of my spiritual life is formed and developed, both in worship and in small groups. I think there are one or two features of the Wesleyan tradition that have been important to me.

What features are those?

One is the way of doing theology. Wesley was never keen on the end point of theology — by which I mean doctrinal statements that some other traditions value. His way of doing theology was to say, ‘It’s more important how you do theology.’ He talked about how you read the scriptures, how you use tradition, how you interpret spiritual experience, how you use reason. Now, those things have been important to me, particularly in integrating science with theology.

What else about the Wesleyan tradition has resonated with you?

Wesley was also fascinated with the future of physical creation. He talked about a new creation, a new heaven, and a new earth. He preached a sermon in 1791, called “The General Deliverance,” in which he talked about the future of cats and dogs and whether they would be in the new creation. That’s an odd sermon to preach, but he did it because he believed in a God who wouldn’t simply throw this universe away, but wanted to transform every part of this universe, not just liberate our souls to heaven, but actually transform the whole of creation — spiritual, physical, all of it — into a new creation. Now, as a scientist, that has been very important for me.

How so?

It means that what is to come is not simply a non-physical thing, not gray, soulless spirits all floating around in clouds, but actually something really exciting. It means that this creation that I study as a scientist is not simply going to be rolled up and destroyed by God at the end of the day; on the contrary, God still has purposes for it. That is key to the Wesleyan tradition, and it affirms the scientific work that I do as well.

Let’s compare the Genesis account of creation with the generally accepted view that the universe is billions of years old. How do you reconcile those two notions as a scientist of faith?

Science and the Bible are different kinds of truth. When I come to the first chapter of Genesis, what I want to do is listen to what that form of literature is, what the writer intended us to take from the text. And for me, the first chapter of Genesis isn’t about the writer setting out a scientific picture. What the writer is doing, I think, is setting forth a hymn of worship. It’s describing who God is. And once I accept that that’s the genre, then I can bring it into dialogue with science.

How might that dialogue play out?

For instance, my science, when I look at galaxies, encourages me to think about the awesomeness of the universe and, therefore, a sense of awe at God. Now that resonates with the writer of Genesis, who is talking about just how awesome the universe is. There’s that lovely phrase in Genesis 1, the understatement of the Bible: ‘He made the stars also.’ God is so powerful that he made a hundred billion stars in each of a hundred billion galaxies! Again, if I’m clear about the nature of scientific description and language and truth, and the nature of the language and truth of Genesis 1, I think I can begin to form a dialogue that comes out of that.

The dialogue never really ends, does it?

Once you begin a conversation of this kind, it’s open-ended; there’s never quite an end to it. You’re always left with questions. You’re always left with insights. For me, that’s what science and theology is all about.

When most people think of faith and science, they think that each is locked in its own silo. What is the future of faith-based interest in science? Is it becoming more popular? If it’s becoming less popular, what can be done to foster a greater conversation between faith and science?

I think the first thing to say is that a siloed model between faith and science is a very recent invention. It only traces back historically to the 19th century. I think we’re beginning to move past that. There are many scientists who are people of faith. There are lots of them who, when they look at the universe, see questions (like) where do the laws of physics themselves come from? Why is the universe so finely tuned for life? They ponder these questions now, even if it might not lead them to become members of their local Methodist church.

What can people of faith do to foster a more meaningful dialogue with people of science?

We people of faith need to be ready to encounter science with humility, joy, and a degree of confidence that we can talk about these things. Our project in the UK, called Equipping Christian Leadership in an Age of Science, allows pastors of large churches and heads of denominations to encounter science in a number of different forms. What we think will break down the silo thing is not something that people outside the church need to do because I think that’s happening. I think that, sometimes, there are people inside the church who need to be attentive and listen to what science is actually saying. And if we do that, we’ll find that, actually, there’s an awful lot to talk about.

To view the lecture in its entirety, go to https://tinyurl.com/ywmydtxx. The password is “n=mr2Wzc.”

Pfeiffer University is extremely grateful to Paul R. Ervin, Jr. for arranging Dr. Wilkinson’s lecture. Ervin is the son of the late Paul R. Ervin Sr., for whom a dormitory on Pfeiffer’s Misenheimer, N.C. campus is named. The elder Ervin also chaired Pfeiffer’s Board of Trustees from 1960 until 1970.