Carlotta Walls LaNier Launches New Speaker Series at Pfeiffer

Carlotta Walls LaNier, one of the Little Rock Nine who integrated Little Rock (Ark.) Central High School in 1957, has called on the Pfeiffer University community to “channel” Gene Earnhardt, the late Professor Emeritus of History at Pfeiffer College.

“Know your history and your country’s history,” she said, echoing one of Earnhardt’s core values. “Know and show your passion within the law. Know that others before you had tough obstacles but were able to stick with their beliefs (and) overcome them.”

Earnhardt arranged for many historically important figures to speak at Pfeiffer, where he taught for 30 years. The Eugene I. Earnhardt Speaker Series, made possible by a gift of the Earnhardt family, featured LaNier as its inaugural speaker on March 21 in Merner Gymnasium on Pfeiffer University’s Misenheimer, N.C. campus.

LaNier’s lecture, titled “My Long Walk to Justice at Central High, 1957,” illuminated the many sacrifices she and the other Little Rock Nine made to achieve integration at Central. It highlighted an eventful day: After her lecture, she met and signed the Central High yearbook belonging to Nona Ehrenberg, a fellow Central High alumna.

Ehrenberg, who now lives in Albemarle, N.C., graduated from Central High in 1958, along with Ernest Green of the Little Rock Nine. When Ehrenberg read in The Stanly News & Press that LaNier would speak at Pfeiffer, she resolved to be in attendance and brought several members of her family with her, including her daughter-in-law Kristen Burdge Conover ’01.

“What happened that year made such a deep impression on a 17-year-old girl that it really set the course for the rest of my life,” Ehrenberg said. “Her presentation was exactly what I expected; it was beautiful.”

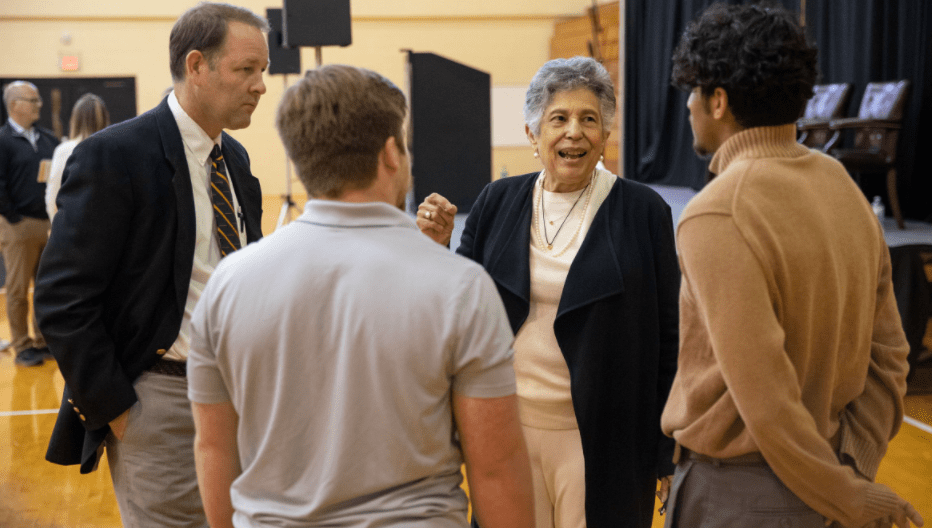

LaNier also participated in a small group session organized primarily for female student leaders at Pfeiffer, teaming up with Dr. Sequoya Mungo, Dr. Michael Thompson, and Dr. Margaret Early Whitt ’68.

Mungo is Pfeiffer’s Teacher Quality Partnership Program Director. Thompson is the principal organizer of the Earnhardt series. He is also a Professor of History and Dean of the University’s Undergraduate College, as well as Director of its Honors Program.

Whitt taught English for 27 years at the University of Denver (DU) until 2009, when she retired as a full professor. She is an expert on the Civil Rights Movement and the short fiction it inspired, and she arranged for LaNier, a Denver resident, to speak to her DU students several times. Whitt also recommended that LaNier kick off the Earnhardt series.

The story LaNier told in her Pfeiffer lecture is rooted in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, a 1954 case in which the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. Brown paved the way for Virgil Blossom, the Superintendent of the Little Rock School District, to come up with a plan for the gradual integration of his district that would begin at Central High in 1957. A limited number of students from all-black Dunbar Junior High, which LaNier attended, and Horace Mann High School could participate.

LaNier said when she learned from a ninth-grade homeroom teacher that she might be able to attend Central High as a sophomore, she signed up without hesitation. She felt comfortable with participating in integration efforts because she often played softball with white and black kids near her home. She also believed that Central High would provide her the best possible opportunities, including more lab equipment and new and up-to-date textbooks (as opposed to the used ones that students in Little Rock’s all-black schools always received).

The teachers at Little Rock’s all-black schools, though “creative” with their limited resources, “didn’t have access to all of the things that were at the white schools,” LaNier said. “That was one of the biggest reasons I wanted to go to Central.”

Unfortunately, the new black students at Central would be able to attend classes only; as Lanier explained in her lecture, there was “a litany of things” they could not do, such as play on school teams, attend football games, or participate in school government — something that LaNier had begun doing before high school to make herself a well-rounded person.

Moreover, achieving the ultimate prize of graduation meant overcoming one obstacle after another. These included the Arkansas National Guard, which barred the Little Rock Nine from entering Central on the first day of school; rioting that (initially) made it unsafe for the Little Rock Nine to remain at school once they started attending classes; and then-Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus’ decision to close Little Rock’s four high schools during LaNier’s junior year.

Remarkably, while the NAACP pushed for integration of Little Rock’s schools in the courts, LaNier fulfilled her junior-year requirements by taking correspondence courses through the University of Arkansas and by earning some additional credits at a high school in Chicago.

During the 1957-58 school year at Central, LaNier was assigned a different military guard each week to escort her from classroom to classroom around the school. This arrangement took hold in late September 1957, after President Dwight Eisenhower decided to enforce Brown at Central with the intervention of troops from the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division and by nationalizing the Arkansas National Guard.

LaNier joked that she became known as “The Road Runner” because, in order to avoid a white student who continually stepped on her heels in harassment, she moved about so quickly that it was hard for guards to keep up with her. On a more serious note, she asked the Pfeiffer students in attendance to imagine the hallways of their high schools filled with military personnel.

“It’s not a good feeling to get educated with that type of environment,” LaNier said. “But, it was necessary then, and I’m happy it did take place, because that way, we were able to get into the school, get the best education we possibly could get under the circumstances, and be there as safely as possible.”

Indeed, safety was always an issue: The Little Rock Nine faced the taunts of a menacing crowd of protesters at the school and the constant harassment by many fellow students. LaNier’s home was bombed in February of 1960, the year she would graduate from Central. LaNier’s father was ostracized to the point where he lost his job in Little Rock and had to find employment elsewhere.

Drew Brightman, a junior from Clover, S.C., majors in history at Pfeiffer and wants to attend medical school after graduation. After hearing LaNier speak, he called her “an inspiration” for persevering in the face of so many daunting trials. He also plugged the educational value of hearing from one of the key figures in the history of the Civil Rights Movement.

“I did have a firm understanding of the Civil Rights Movement as a whole before I heard her lecture,” he said. “But hearing her personal account increased my depth of understanding of the movement.”

Casey Habich and Landon Orrand ’23 contributed to this article.