A Pfeiffer ‘Prophet’ Powers Forward

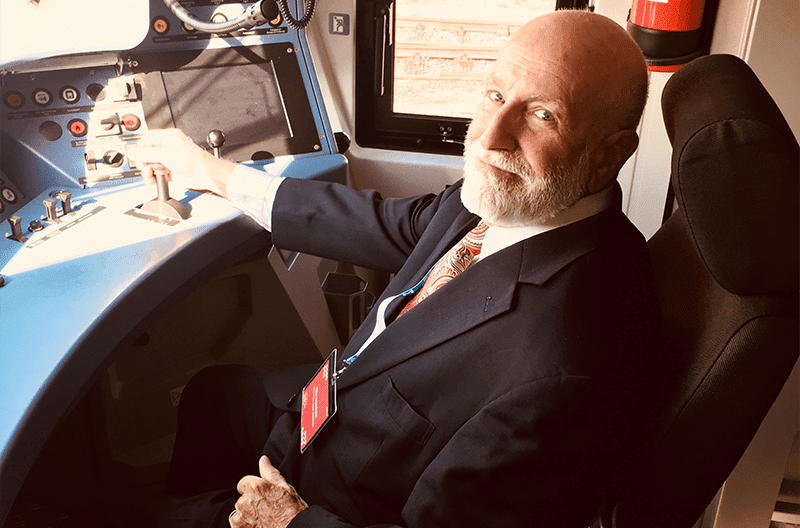

More than 13 years ago, when officials with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency were discussing North Carolina’s air quality problems, Pfeiffer University alumnus Stan Thompson entered the scene.

Thompson, who graduated from Pfeiffer in 1962 with a degree in English literature, had been a long- time activist for improving Charlotte’s air pollution. He retired in 1996 after decades spent serving as a strategic planner and environmental and transportation futurist at Bell South (now AT&T).

Thompson’s work experience led him to hydrogen-powered rail technology: a means of powering trains by converting the energy of on-board hydrogen to mechanical energy, either through the use of an internal combustion engine or by reacting hydrogen with oxygen in a fuel cell.

What the technology means for the average person is cleaner, cheaper, highly available energy that’s better for both people and the environment.

Thompson coined the term ‘hydrail’ for the technology in a 2004 article he wrote for the “International Journal of Hydrogen Energy,” about the same time that he teamed up with Jason Hoyle from Appalachian State University and former Mooresville mayor Bill Thunberg to create the Mooresville Hydrail Initiative.

The Initiative started with three goals: to help the greater Charlotte area meet federal air quality standards, to find funding for a commuter rail to be built on the 28-mile track from Charlotte to Mooresville, and to bring new employers and jobs connected to the hydrogen economy to the state.

Linda Rimer, currently a state and community resilience liaison for the U.S. EPA-Region 4 Water Protection Division, said Thompson added an important environmental component to discussions about reducing air pollution.

“I’ve been a fan of Stan for many years,” Rimer said. “The EPA supports him. He cares about air quality, and he cares about the environment, but he’s also a businessman.”

The collaboration between Thompson and his stalwart team of two led to the hosting of the first International Hydrail Conference in 2005 in Charlotte. The purpose of the conference, Thompson said, was to bring together scientists, engineers, business leaders and industrial experts and operators to expedite hydrail’s adoption.

“The way we brought this about was by convening the first pioneers around the world,” Thompson said. “We found all the people with the information and put them in a room together and let them talk.”

Interest in hydrail exploded. Eight countries— the United States, Denmark, Spain, Turkey, Canada, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Germany— have hosted the annual conferences, which have taken place every year except in 2011, due to the recession.

“Stan has been the energy behind it all,” Thunberg said. “He never stops. It’s a passion for him. He really believes that there’s no limit to what you can do if you’re persistent.”

Thompson has traveled to 10 countries, on invitation, to present about or participate in discussions about hydrail technology. He said the international aspect was not “the original idea”—which was to premiere the technology in Charlotte to help with the city’s air quality problems.

But Thompson ran into unexpected opposition in North Carolina as early as 2000, when he first brought up the topic of hydrogen-powered rail technology at a Charlotte Chamber of Commerce meeting and to local media.

Rimer, who also was responsible during her career for federally-delegated and state environmental regulatory programs for air and water quality, said she still does not understand the reason for that resistance.

“He was trying so hard to create good jobs in North Carolina, and he and his team worked so hard to make sure that this technology stayed in the public domain,” Rimer said. “But Stan could not seem to get people to pay attention. The only thing I can think of is that Bible quote, about a prophet not being recognized in his own land.”

Rimer added, “I don’t know many people who would have continued on. But when Stan hit a wall in North Carolina, he went other places.”

Thunberg said he believed Thompson persevered for a simple reason: he knew that what he was promoting was “right.”

Two countries already are using hydrail technology: a factory in Salzgitter, Germany, is producing hydrail trains for Europe, and China is producing hydrail trams in Qingdao and Tangshan. Thompson said 17 other countries also have announced hydrail plans.

“I’m better known in Shanghai than I am in Charlotte,” Thompson said, chuckling. “I have people around the world trying to help me.”

In addition to his international outreach, Thompson continued to raise awareness locally through public radio and TV appearances. He also spoke to students at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

North Carolina’s Department of Transportation only recently announced, in September 2018, that the department is seeking funding to convert Piedmont passenger trains— running from Raleigh to Charlotte— from diesel fuel to hydrogen fuel cells.

Thompson, though delighted by the development, also expressed his regret that he couldn’t convince the state to pursue the technology sooner.

“What’s really incredible is that we’ve been doing this for 15 years,” Thompson said, “and people are only hearing about it now.”

Thompson also served as the head of the Mooresville/South Iredell Chamber’s transportation committee in 2003, was a plenary speaker at the EPA’s Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards “Air Toxics” conference, and is a member of the World Affairs Council of Charlotte and the Charlotte Economics Club. He also is a member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, the American Institute of Archaeology, and the American Council on Germany.

A favorite pastime, however, is his regular column about history, politics and economics for the Mooresville Tribune, which published his 300th piece in December.

Thompson said his roots as a columnist stretch all the way back to his days at Pfeiffer University, where he wrote a column called “Counterpoints” for Pfeiffer news.

At the mention of Thompson’s alma mater, Rimer paused thoughtfully.

At the mention of Thompson’s alma mater, Rimer paused thoughtfully.

“I don’t know if it was Pfeiffer or something else,” she said. “But something has placed a drive in this man.”